On the banks of the high glacial river in the Swiss Alps, in an underground stone room in the remnants of a 12th-century Benedictine monastery, one can find photos of Gabriel Stoize.

These images are small and basic and are often exposed to edges. The artist is young, often without clothes, her body is bound in twine or covered with clear viscous liquid. She painted it directly on portraits of herself or friends. The flowers sprout from the naked buds of Nora. The characters of the Satanites rise like ash smoke. From the glass box, the ceramic eyes stared at the broad witch, vine-like nerves-attached to the li feet, the inanimate tongue.

What would the young Gabriele do with such a show? I asked Stötzer in Zurich the day before the exhibition, titled “MIT Hands and Fuss, Hart and Harr (with hands and feet, skin and hair) open in Muzeum Susch.

“She will be impressed,” Stitzer told Artnews. “I think the basic power of this place will attract her.”

The museum occupies a site once crossed by pilgrims, heading to Santiago de Costela in Spain. In the surrounding meadows, local farmers would still say Romansh, an ancient form unique to the valley. However, this place is also of great significance to the elites in the world. After walking along the Hotel River for a day, I soon arrived in Davos. The valley sat down along St. Moritz.

Muzeum Susch was founded by Polish entrepreneur Graêna Kulczyk, who dug over 10,000 tons of rock from under the monastery in 2015, creating approximately 15,000 square feet of gallery space. There are chambers, walls and rocky walls, some are wet walls that seep from the Alps.

Kulczyk mainly uses this Gothic environment to highlight the work of the female artist behind the Iron Curtain – her generation is often forced to work in secret, worried about the glare of informants and official surveillance. “Most of it lives in my cabinets and drawers,” Stotzer said of the works in the exhibition.

It was the first time a major institution has presented a solo exhibition for the artist Stötzer, forged on the edge of the East German, whose work violated the unfortunate patriarchy of the German Democratic Republic (GDR), and the Ministry of Security paranoid, Stasi.

Daniel Blochwitz, the show’s curator, told The show Artnews. “Some people’s lives seem to collide with power from a very young age. I don’t think her moral compass has little or no deviation at all.”

Gabriele Stötzer

Daniel Blochwitz/ courtesy of Muzeum Susch

Blochwitz said Stotze was under such a scrutiny that she could now have a place in the historic canon. “She is just beginning to be recognized as a major figure in global art history.”

Born in Emleben in 1953, Stötzer was expelled from the university at the age of 23 and was sentenced to one year in Hoheneck Women’s Prison, due to housing political prisoners and her words, “the murderer, violent women, thieves, thieves, bank robbers”. Her crimes signed a petition to defend exiled singer-singer-lyricist Wolf Biermann, or, in GDR’s words, “the slander of the state.”

“I knew early on that my body was the only medium I left behind,” she said. “One thing I can rely on.”

In her memoirs, Stitzer describes how her physique changed when she was imprisoned. Faced with the official indifference to prisoners’ health, the threat of violence, and the sight of women’s self-harm, she began to lose her hair, her skin turned red and harsh. Therefore, the title of the Susch exhibition is almost personal.

“But I was one of the only women in prison who could talk to everyone,” she said. “Before Hoheneck, I thought only men were able to murder. But I met a lot of female murderers in prison and I had to understand what was driving them. I knew them, too. They became my community.”

In her release, it was obvious that she would be deprived of materials, banned from exhibiting at the GDR Museum, and refused to enter the art school. However, Stötzer works firmly with the state-approved GDR cultural space and the sneakyness of Stasi, she remains a dissident in the growing interest.

“She was deprived of resources and was subject to relentless surveillance,” Blochwitz said.

Her photos are assembled from anything she can remove: sheets on the background, makeup of the shoe polish, natural light. After becoming friends with local sheep farmers, she made textiles from wool. To get through, she made jewelry from scrap metal and sold it on the street market. “I used everything around me,” she said.

French curator Sonia Voss Artnews The artist “was caught between the instinct of self-destruction and the creative potential of self through the destructive power of magic, dreams and fantasy of the female body. All of this lacks a few props: a mirror, a roll of bandages, a roll of bandages, a little paint.”

In the early 1980s, Stötzer helped find the radical feminist collective exterior XX, whose members created Super-8 film and photography series carefully copied in office photocopiers and distributed among friends. The group conducted fashion shows and experimental performances in the apartment, with few records. Some of her collaborators openly lived normative lives as mothers and wives and worked as secretary or offices of low-level bureaucrats, but once in the security of the Sterze apartment, their bodies were painted with paint.

“These women did not call themselves feminists at the time,” Voss said. “But they were clearly trying to get rid of patriarchy and dominate even in the underground art world. It was about self-exploration, self-empowerment, shared discovery among women, and courage to express their desires among women. They ultimately helped reshape the socio-political environment behind the wall.”

Stotz also works with men. A friend likes to take pictures on his clothes. She later discovered that he was a Stasi informant.

“I was shocked, but I wasn’t surprised,” she said. “You know Stasi is watching.

Betrayal has different revelations for the 1984 photography series, and the man confidently encounters her camera. Years later, Stetzer discovered that this supposed outsider (only Winfried) was watching her.

“Stasi took advantage of the fact that he was different,” she said. “They used it to oppose him.”

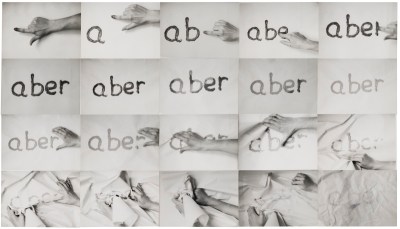

Gabriele Stötzer, Aber Heilerde1982, 2023. Galerie GiselaClement.

Galerie Gisela Clement/Provided by Muzeum Susch

Stezer’s work developed in parallel with Nan Goldin’s, which became synonymous with Berlin decades later. Gold’s breakthrough participated in the 1981 exhibition New York/New Wave In MOMA PS1 (then called PS1 Center for Contemporary Art), this is due to the creation of many works by Stötzer on Susch. Their art shared a lot, but Stotzer was not aware of her contemporary throughout the Atlantic Ocean.

“East German artists, especially women like Gabriel, have fewer opportunities to interact with external ideas,” Kurchik said in a statement. “Her experience is marked by double isolation – from the state-recognized East German art and the West.”

Stitzer’s role expanded to her studio. In December 1989, with the fall of the Berlin Wall, she participated in the occupation of the Stasi headquarters in Erfurt, helping to protect important surveillance archives.

“I wanted to take my personal files, but then I saw all the other files – rows and rows. You want to trust people, open and undoubted. But, it made me realize people’s abilities.” She described how her group blocked the door with her body, asking for documents to be protected. “I thought, even if they shot us, at least I did the right thing.”

In recent years, Steze’s work has gradually begun to gain mainstream recognition. She was awarded the Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany in 2013, and her photos included in Documenta 14 in 2017 “A restless body: East German Photography 1980–1989” Rencontres D’Arles in 2019. In 2023, her work played a central role in the exhibition.Various Realities: The Experimental Art of Eastern Group” At the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, she stands out among nearly 100 artists working in Soviet-controlled Eastern Europe.

Stitzer’s art reminds us that aesthetics and politics are inseparable, and this resistance exists not only in protests, but also in the materials we choose, the words we use, the actions we record.

“Feels, thoughts, passions, they all exist in every society,” Stotzer said. “Anyway – they are always present and they can’t stop.”

Gabriele Stötzer: MIT Hand & Fuss, Haut & Haar has been visiting Muzeum Susch in Switzerland until November 2.

Follow Me