Can sculpture convey power? Historically, sculpture has been one of the key ways to portray who is responsible and worth remembering. In the United States, the Lincoln Memorial and Mount Rushmore recall the country’s most respected president. Sculptures were tools for conveying power, and the rise of monuments was seen in the wake of the Civil War and in the early 20th century. For many of these sculptures, it is alienated and oppressed. In the past five years, many protests have called for the cancellation of many statues, from Louisiana to Virginia to Georgia. By looking at the public monument of white people celebrating the history of this country, we can see who celebrates in particular.

The Smithsonian Museum of American Art’s “Shadow of Strength: A Story of Race and American Sculpture” (until September 14) aims to subvert this history, showing the views of artists from various backgrounds who have taken their sculptures to root. Here, everyone has strength and import.

The exhibition offers a new look at American sculptures, which companion Karen Lemmey said remains a part of art history. More than half a century ago, the last major American publication in the United States was published.

“There is indeed a wider interest in monuments, public art and sculpture,” Leme said. Artnews. “There aren’t a lot of resources, people ask questions, and I inevitably go back to the last big survey, which isn’t the latest.”

The exhibition created 82 works of art by 70 artists between 1792 and 2023, divided into nine themes, including “Family and Racial Identity”, “Unity and Resistance”, and “Classics and Myths of White Ideals”.

After attending the exhibition, the audience encountered a video that included Tobias Woffard, an art historian at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, who questioned the concept of sculpture and its relationship to power. He raised three questions about sculpture, race and power, and asked passersby at the National Mall, such as “What do you think when you hear the word power?” One answer: “Power can be shared.” This response sets what visitors are about to see, the sculpture is created by diverse artists and tells an inclusive story.

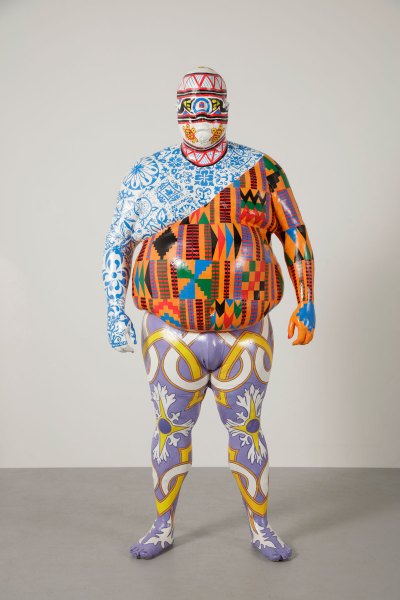

Roberto Lugo, DNA research reexamination2022.

Smithsonian American Art Museum

The show is open in four different sculptural methods. Roberto Lugo DNA research reexamination (2022) is a life-sized self-portrait sculpture of the artist, depicting his racial makeup, which is portrayed through various culturally representative textile patterns. Titus Kaphar’s Commemorative Reversal: George Washington (2017) shows that the first president of the United States is right away. Rather than creating a round, highly polished bronze sculpture, Capal displays Washington and his horse as unfinished, steel-coated figures embedded in a piece of wood. Below, hand-blown glass representing horse legs lie on the floor.

Nearby is Alison Saar’s 2006 mixed media statue, a girl stares at the frying pan Mirror (Mulatta seeks inner negatives))the artist’s reflection on her mixed schedule. Hanging on a wall Many ways to be human (2020), a meticulous arrangement consisting of 30 black and white, hand-shaped clay figures, each of which is about 10 inches tall, and is about 10 inches tall by Anita Field (Osage/Muscogee). In each of these artists, sculpture becomes a reflection of the collective identity of the country.

“Sculptures can be this incredible form that can be reflected on through these big ideas,” Leme said. “Race is an experience of life, an exhibition that encourages dialogue but introspection. So each of these four sculptures is done in a different way.”

Starting from left: Hiram Powers, USA1848-50. Sanford Biggers, Lady Interbellum2020.

Smithsonian American Art Gallery (2); right: Photography by Lance Brewer/©Sanford Biggers/Petitive Artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York and Aspen

But the curator also matches contemporary works with historical works. Neoclassical plaster sculpture by Hiram Powers USA (1848–50) shows a naked woman with her hands raised and her feet stomping on the chain as a representative of the United States. Nearby is Lady Interbelluma 2020 marble sculpture, created by Sanford Biggers’ crouching Venus, created by combining 3D scans of Central African style ancestors and ancient Roman sculptures. Everyone describes the image of women as a representative of nationalist ideals: USA For former audiences who have not yet opened to the end of slavery; Lady Interbellum In another hostile moment, contemporary audiences.

“I have some intentions,” Biggs said of the motivation behind it. Lady Interbellum. “One person is interested in work based on classics. Of course, when I say classics, I mean Western Europe, and also artworks from various African countries, because I think these works can also be regarded as classics. They have a great influence on contemporary and modern art.”

The Shape of Power also includes a special focus on black female sculptors, showing off their ancestry from the 19th century to the present day, as well as the works of Edmonia Lewis, Augusta Savage, Betye Saar, Barbara Chase-Chase-Riboud, Joyce J. Scott, and Simone Leigh. Their agility in formal skills matches their conceptual abilities. Lewis’s 00 in the wildernessThis is a lifelike marble statue that tells the statue created by a racially ambiguous woman in 1875, depicting the biblical story of Hegar, who was immersed in her slave husband, a story related to the recently released black woman who might have thought of when she was doing the job. Leigh created sculptures about 150 years later, making the head summary of the black female image, so it was almost unrecognizable, waving the power of her making the black female identity known.

Simone Leigh, Country Series2020.

From Kelly Williams and Andrew Forsyth

The Family and Race Identity section describes how artists use sculptures to deconstruct race as a fixed homogeneous category. LAS chainThis is the 1998 installation of Pepón Osorio, showing off twin sisters, one black hair and a light blonde hair. They sat on swings, dressed in beautiful white communion dresses, boxing gloves, and decorated on Puerto Rican flags. Osorio points to the absurdity of racial classification based on body appearance, especially in the Caribbean, while also emphasizing that racism and colorism are everywhere in the Latino community.

Racism in society and its violence suffered are the themes of several other works, in the form of “power” Curtull (1939) Russian-born sculptor Aaron J. Goodelman immigrated to New York in 1905 and escaped the Jewish Massacre. The five and a half feet sculpture is made of polished Pierwood and found iron chains and chains, depicting an abstract figure with hands above them bound, a clear condemnation of the lynching. Goodelman, a registered communist, reached a similarity between African-American lynching in the United States and the rise of anti-Semitism in Germany in the 1930s. (The title of the work refers to the ideology of Nazi cultural superiority; however, Goodman relates this culture to one of the violence.)

Aaron J. Goodelman, Curtull1939.

©1940 Aaron Goodelman/Smithsonian American Art Gallery

According to the Wall text, Goodman’s sculpture is a feature of the exhibition’s “Unity and Resistance” section, “condemning the extensive lynching of African Americans in America.” Nearby is Nari Ward’s swing (2010), a car tire with a toe, tongue and rope. Although the tire swing may indicate a toy, the rope it actually hangs is actually a noose. The pairing of these two artworks expresses solidarity through a shared mission of condemning racial violence. Lemmey’s work like Goodelman’s says: “Early evidence shows interracial solidarity and protesting communities. We might envision a monument as how various communities consider using sculptures to represent or represent a representation of a thought, if not self or community.”

“The Shape of Power” ends with an optimistic note with a section titled “The Story of the Future.” Young Joon Kwak’s 2023 The sacred ruins (My face copper) The bronze medal showing the artist’s face, their eyes closed as if they were sleeping. Its appearance is as shocking as White Hinnistone. From the dream of quark (Kwak), a more realistic form of the future.

Nari Ward, swing2010.

©2010 Nari Ward/Smithsonian American Art Gallery

However, this work includes not only contemporary future predictions. The works included are Ethiopia Awakens (1921), 12-inch Maquette by Harlem Renaissance artist Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller. The artist describes an elegant woman as a relic of the past, aiming to symbolize the imaginary future of African Americans. “This is a group that once made history,” Fuller once said of the work, “now wakes up from a long sleep, gradually relaxing the bandages of the mummy’s past, looking at life again, looking at life again, expecting, but not afraid, at least with an elegant posture.”

The 82 artworks in the exhibition cover 200 years of art history, from palms that can fit the palms to monuments that stand on the audience. They come in a variety of media, from durable wood to fragile ceramics. The diversity of vision here ranges from the creator to the form of the work and its meaning. A new understanding of the inherent power of sculpture emerges. This is a true description of the United States and what it may be.