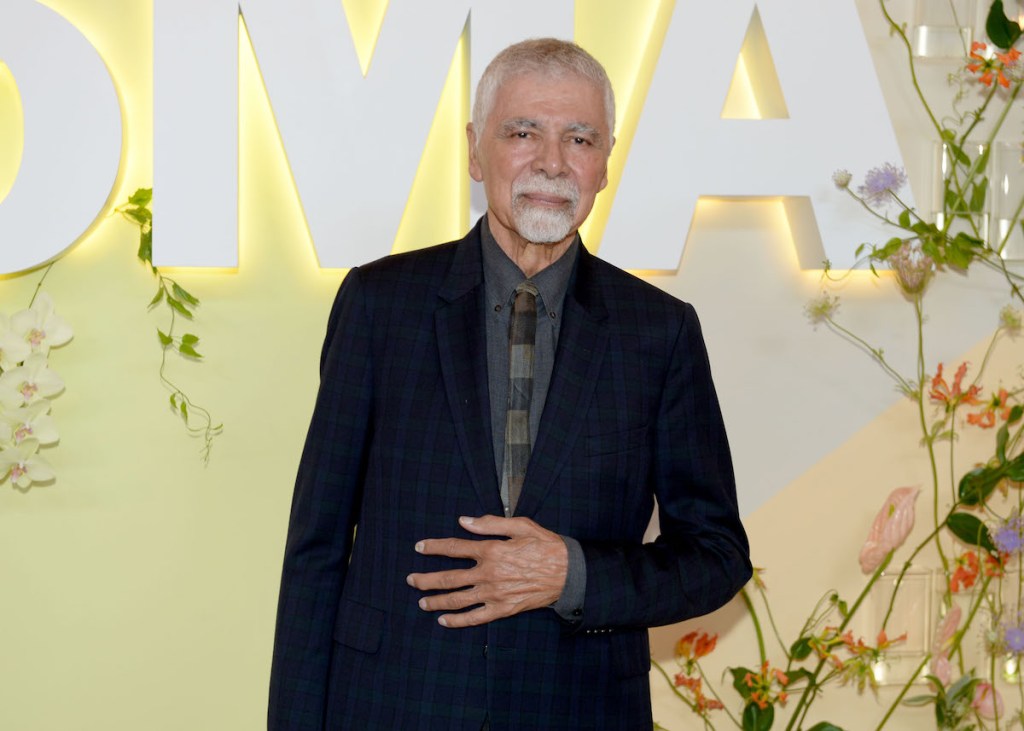

The artist John Woodrow Wilson (1922-2015) once said he was a black man who had endured “a kind of slow death.” How to best fight that protracted, frustrated violence? For Wilson, one solution is to produce art.

In his paintings, sculptures and prints, he often deals with oppression head-on. Early in his career, he created shocking racist violence, workers’ rights movements, and the dissatisfaction he portrayed. Starting from 1945, an unforgettable painting of a black man bent over a table with his hands surrounding his head. Its title Black despair.

But by the end of his career, he had transitioned to a different, seemingly milder pattern. He repeatedly attracted people he knew in Boston, where he was born and what he spent a big part of his career. For Washington, D.C., he created a particularly memorable piece of public art, the first memorial of Martin Luther King Jr. to occupy the Capitol.

“In the past six decades, from the earliest work he did in school, he has been fighting for the authentic and positive representation of Black Americans, and his attitude is to elevate his subjects, whether they are family or friends, people in his community or iconic public figures,” said Edward Saywell, chairman of the Printing and Drawing Department of the Museum of Fine Arts, chairman of the Printing and Drawing Department. “Most of his work is about seeing the visibility of the Black experience. ”

Saywell is one of three curators behind the Wilson retrospective that opened in MFA Boston earlier this month. In Boston, Wilson is a local legend. But apart from that city, his reputation is not quite certain. That’s why when the show travels to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, its co-organization, this fall, it can solidify Wilson’s historically excluded Canon. “We felt deeply and passionately that he really needed to see him on the national platform,” Saywell said.

Wilson did not succeed in his time. He is a friend of sculptor Elizabeth Catlett, the godmother of the child. He maintained a close relationship with Robert Blackburn, who worked with Catlett, Romare Bearden and many other notable artists, and later served as the best man at Wilson’s wedding. He won the highest honor at the Art Art Younnal at the University of Atlanta and was once considered the most important repetitive black art exhibition in the United States. Artist Charles White chose Wilson in a jury. His works were early acquired by institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art.

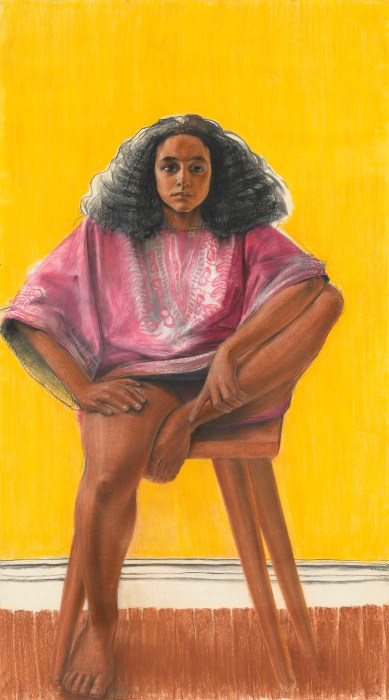

John Wilson, Young American: Gabriel1975.

© John Wilson Manor/Washington National Art Gallery, Boston Museum of Fine Arts

Many Black Modernist investigations have been conducted since Wilson’s death, but overall, they have no works. Saywell and his companions – Patrick Murphy, MFA’s printing and painting curator, Leslie King Hammond, and met Jennifer Farrell, a curator of print and painting, raised some potential reasons: Wilson worked in symbols, not abstractions; he was often stationed outside New York, the national art capital of the time. In and outside of the academic environment, he worked as a day job as an art teacher to support himself and his family, which often disengage him from the studio.

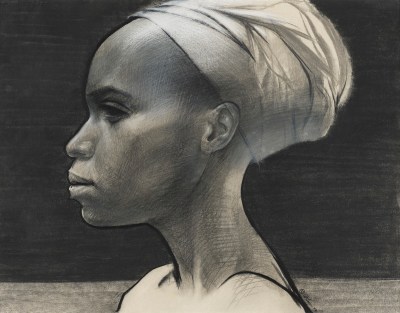

King Hanmond proposed another factor: in the eyes of the shapers of art history, his focus on humans rather than formalism is not formalism. “He was very clear not to harm the information he was trying to create, it was about his obsession with the anatomy and the human body – whenever you see a person, you see something new, different or amazing,” she said. “He wanted to legitimize it to maintain it, give honors, bless it with the right stroke and the right gesture.”

John Wilson, ROZ No. 9, Research on Eternal Existence1972.

© John Wilson Manor/Photo © Boston Museum of Fine Arts/Boston Museum of Fine Arts

Throughout history, we have been familiar with many artists who have done similar things. “You know, when Rodan does this, we have no problem with that,” Kimmond continued. “When Leonardo did this, we had no problem with it. It was John Wilson of Central Boston,” with what she said “energy and visionary he called when he faced a ruthless overthrow.”

Wilson was born in Roxbury, a black population in Boston, from two immigrants who were then known as British Guiana. Encouraged by his father’s study in art, Wilson took classes at the Museum of Fine Arts School, and his teachers were all white. He walked through the museum gallery and was shocked by what he saw: the image of a white man. Wilson once said: “This means that black people are not capable of being beautiful, real and valuable. . Black people and their special experiences do not matter, they do not matter.”

He will devote his career to solving this problem. First, he would rely on the language of social realism to criticize the problems troubled by his community. Black soldiers (1943) is a painting on the MFA program that includes a black family separated from World War II. Father faces the Statue of Liberty, a symbol of his patriotic obligation, literally looking at his wife and children. The husband and wife are staring at us, longing for better.

John Wilson, Black soldiers1943.

© John Wilson/Clark Atlanta University Art Gallery, Atlanta/Museum of Courtesy, Boston Museum of Fine Arts

Then, by the end of the 1940s, he will briefly try to use completely different abstractions. He graduated from Tufts University in 1947 with a degree in education and received a grant to Paris. There he trained under the leadership of French modernist Fernand Léger, known for his so-called test tube style, in which people seem to be formed from mechanical elements. Wilson started working in a way similar to Léger’s, drawing a combination of blue and red color palettes with uneven shapes. But Wilson’s abstraction is too picky. They weren’t as relaxed as his social realists did.

This could explain why when Wilson got a grant from Mexico City in 1950, he returned to realism and made prints that did not shy away from harsh labor conditions. He studied among the popular men of the higher De Gráfica, and his work began to flourish, which flourished from modernists such as Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco. These new symbolic works are as dazzling as before. His terrifying 1952 mural eventthe study appeared on the MFA show, depicting a black family covering themselves at home while a black man was lynched by Cransman outside.

John Wilson, Campesinos (Farmer), 1953.

© John Wilson Manor/Photo © Boston Museum of Fine Arts/Private Collection

Metropolitan curator Farrell, who co-organized the retrospective of the current Wilson, said the works, while back to conception, were different from his work in the early 1940s. “He felt the real responsibility was to provide positive representation. I think that’s why he didn’t go that purely abstract route,” she explained. “But it’s interesting to watch his works made with Léger, and then in Mexico, they have very powerful abstract elements, positive and negative patterns and break things down into pure geometric forms. They’re still there.”

Wilson returned to the United States in 1956, resided in New York, and then moved back to Boston in 1964. That same year, he began teaching art at Boston University, where he continued until 1986. He will never forget the reality of being black in America: his wife is white, they are white, and they have to ride separately in mass transportation. But his art becomes softer as he seeks new ways to provide black people with new ways to dignity rejected by mainstream media.

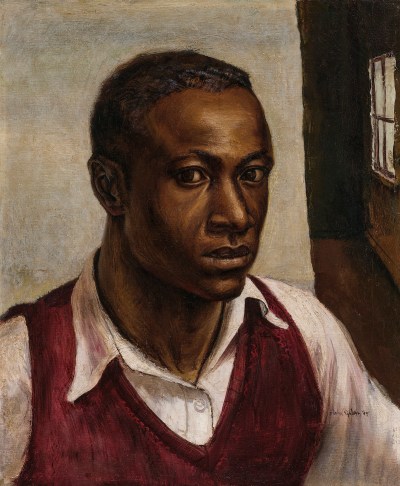

John Wilson, Self-portrait1943.

© John Wilson Manor/Photo © Boston Museum of Fine Arts/Boston Museum of Fine Arts

In the mid-60s and mid-80s (a period roughly consistent with his years), his achievements included the cover of books on Malcolm X on Children’s X and many drawings of his children, friends, and people in the community. These drawings are rich in observed details: flared jeans, these jeans on sneakers, a lot of hairstyles, tightly knotted turbans. “You’ll see him dealing with the challenge of capturing the present, gestures, characters, personal troubles,” King Hammond said. “You want to know: how many days he worked with this particular topic, and how many times he tried to reassess how to introduce or portray this person?” She said he was fascinated by teenagers because he saw them as “the leaders of the future.”

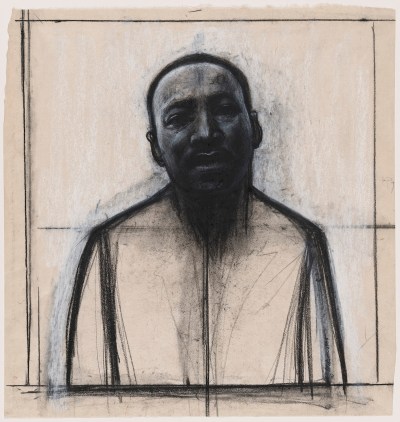

John Wilson, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.1985.

© John Wilson Manor/Photo © Boston Museum of Fine Arts/Boston Museum of Fine Arts

Now, with the work of a new generation of black metaphor painters gaining recognition, Wilson’s art is spending his day. The current retrospective is a coincidence in some ways: Farrell discovered when he proposed the exhibition that MFA had curated a similar Wilson exhibition, thus giving birth to a collaborative speech. She said it was a happy accident, which she described as a coincidence because contemporary artists were talking to his art, whether they knew it or not. “I think a lot of artists have drawn inspiration from Wilson, or the issues Wilson had involved in the 40s,” she said.

The exhibition catalogue meditates on the meditation of Wilson’s art by Amy Sherald, Napoleon Jones-Henderson and Derrick Adams. “Wilson” is my mission to understand what I expect from Americans, not from blacks, while leaving behind a culture that we fully represent. “Wilson’s contribution to art history has been almost erased in institutions such as MFA and MET, leaving his work invisible to most people. Wilson, an artist who fears “slow death,” has now officially found a second life.