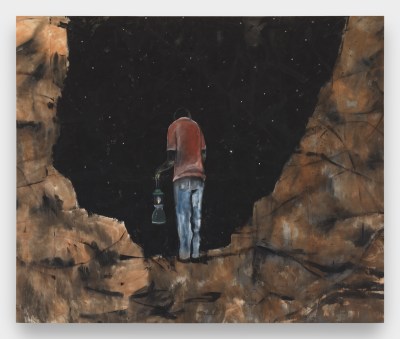

exist Drawing for my dad (2011), artist Noah Davis introduces a man’s figure, staring at a rocky landscape under an interstellar, almost black night sky. As the figures move away from the audience, wearing worn red shirts and jeans and holding barely illuminated lanterns, the artwork is solemn. Davis created it the year his father, Keven, died of a brain tumor.

“It is not clear whether we are looking at it. [Davis] Eleanor Nairne, head of modern and contemporary art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, noted. Davis herself has become a parent, she added, “so it’s poignant.”

Noah Davis, Drawing for my dad2011

Collection of Rubell Museum. Copyright © Noah Davis’s property. Provided by the property of Noah Davis and David Zwirner. Photo: Kerry McFate.

This month, the Barbicans in London will host the largest survey of Davis’ work at a travel exhibition last fall at Das Minsk Kunsthaus in Potsdam, Germany, and will move to the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles in June last fall.

“There are two aspects of Noah Davis that we celebrated in this exhibition. He is an innovative painter. “The second aspect is that he was involved in the Underground Museum, and he co-founded him in a disadvantaged suburb of Los Angeles with his wife Karon Davis.

Davis was born in Seattle in 1983. He moved to New York to study at the Cooper Union Academy of Arts, but left before graduation and moved to Los Angeles in 2004. There, he continued his art journey, learning from exhibitions, catalogs and creative individuals while working in a bookstore at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA). A few years after his father’s death, Davis himself died of cancer at the age of 32, leaving behind a legacy rooted in his indestructible drive to enhance his community.

Drawing for my dad Both are contrary to most of Davis’s work. Similar to many of his works, the central figure is black, the painting is emotionally complex, with the subject being somewhat rejected or ambiguous. However, it also atypically incorporates the house in the personal life of the artist, and uses a pastel palette that contrasts with the more vibrant works he is known for.

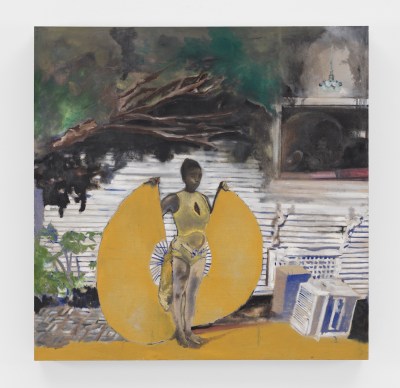

Noah Davis, ISIS2009

Mellon Foundation Art Collection. Copyright © Noah Davis’s property. Provided by the property of Noah Davis and David Zwirner. Photo: Kerry McFate.

Like his works Drawing for my dad Explain how Davis finds beauty and mystery in everyday moments through tender but emotional images. Another example is The last barbecue (2008), depicting a relaxed social gathering, conceptually familiar and mysterious, in some mean composition.

“His interaction with what reality presents and what is built or manipulated is all about,” said Barbican curator Wells Fray-Smith. “In these works, he struggles to deal with everyday life, and that it looks real, but also totally incredible or weird.”

Nairne added that the works create a “intimacy” while giving the impression of “a semi-memorial dream.”

The painting dedicated to Davis’ father also emphasizes how the artist has a profound understanding of art history, which he often incorporates into his work, sometimes even more cleverly. “He was influenced by various artists, from Édouard Manet, Paul Cézanne and Mark Rothko to other artists like Romare Bearden, Caspar David Friedrich, and artists who are not painters but are doing new things or breaking up with conventions,” Fray-Smith said. “For example, he likes the minimalist sculptor Donald Judd, who was captured by people who created their own world in some way.”

Noah Davis, Missing link 42013

Collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Copyright © Noah Davis’s property. Provided by the property of Noah Davis and David Zwirner. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer.

Influence Wanderers above the fog sea (1818) Caspar David Friedrich on how Davis positioned its theme in Drawing for my dad Like Friedrich, confronts the vast rocky landscape. “The kind of parallel images you might find in historical paintings and then perfect them in Davis’ paintings,” Fray-Smith noted. “He is seeking to connect everything he has experienced in everyday life with all the representatives he has encountered in art history, too.” Fray-Smith believes that the “missed link” he explores is “bold.”

“In this series, he reimagines paintings we might know from the history of art, e.g. [paintings by] Rothko or Manet and combine these works with black characters. “We can see these numbers in leisure, rest, and through the modernist landscape. ”

Helen Molesworth, a curator in Los Angeles, remembers that she was surprised when she met the artist in 2014. “The current fashion or fashion of the black metaphor painting we live in isn’t like that,” Morseworth said, working at Mocha at the time, “it all happened after Noah’s death,” she added after the museum’s first major retrospective, Noah’s death in 2017.

“When I first met Davis’ work, one thing I saw for me looked completely different to what other people did at the time,” Morsworth said. “It’s not that the black image doesn’t exist at all, but that it happens in photography, not in painting.”

Noah Davis, Untitled2015

Collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. CopyRight©Noah Davis’s property. Provided by the property of Noah Davis and David Zwirner. Photo: Kerry McFate.

Not only was Davis keen on putting Black people front and center in his work but, when Molesworth met the artist, he was working on making art more accessible to marginalized communities, having recently opened the Underground Museum (UM) with his wife, Karon, in 2012. Using his inheritance from his father, Davis rented four storesfronts in Arlington Heights, a disabled Black and Latinx suburb of Los Angeles, converting them into freely accessible art space. (The museum ceases operations in 2022.)

Molesworth itself regards UM as a work of art, likening it to the concept of Germany gesamtkunstwerksee multiple art forms and experiences jointly achieve artistic goals. “It’s ‘all the artwork’, because Noah has built the space,” she said. “He left the garden plan; he built a bookstore. It’s a total atmosphere. She continued, “Even the bathroom is full of art.”

“When people walk into the space, they feel it right away — it doesn’t have any conventions in contemporary art space,” she added. “I thought, ‘Well, that’s art.’”

Davis convinced Molesworth to lend his work from the Moca series to show in the space, prompting her to give him a copy of Moca’s “Bible,” a huge adhesive that contains all the works in the institution’s permanent collection.

Installation view, “Imitation of Wealth,” Installation view of Underground Museum, 2013

Copyright © Noah Davis’s property. Provided by the property of Noah Davis and David Zwirner. Photo: Karon Davis.

“He can use all 7,000 items,” Fray-Smith explained, noting that he curated 18 shows, although he was able to see an implementation before his death, a solo speech by South African artist William Kentridge.

“He joked that the first African to be held at UM was white,” she continued. “I think he saw the humor.” Not only was Davis interested in exciting artists, but he was also passionate about cultivating those who visited UM by providing a range of art for UM.

Although he tells his art and his life’s black artists and marginalized communities, Davis downplays the political aspects of his work, as he tells sleepy In 2010. “Race plays a role in black people as far as my numbers are concerned,” he said at the time. “If I make any statement, it is to show black people in normal circumstances that drugs and guns there are no connections to it.” That is to say, he never shy away from political topics, nor denies the power that art can bring when inciting change, and sometimes surprises people how it is treated in practice.

In October 2008, Davis was titled “Nobody” in the 1905 Bert Williams song after the book “Nobody” by Roberts & Tilton, now the Roberts Project. Each of the works in “2004” depicts a flat geometry of dark purple, one in Colorado, another in New Mexico, and the last in Nevada, in 2004 by John Kerry and George W. Bush.

Noah Davis, Seventy works (36)2014

Copyright © Noah Davis’s property. Provided by the property of Noah Davis and David Zwirner. Photo: Stephen Arnold.

“He was keenly aware of the white gaze and what the world of art expected of him, mostly white,” Fray-Smith explained. “He got rid of symbolism and abstraction, a way to avoid the burden of racial burdens, and explored how his work became political without visually clear.”

Davis manages to carve a powerful legacy for himself, and he still works on his dying job even though his life is severely shortened. “I probably spent more time in the hospital and Noah at some point discharged,” Molesworth said. “He was an incredibly ambitious young man who knew he was very sick and he tried to do as much of his work as possible before he died while also accepting the fact that he was dying.”

She noted that Davis changed the lives of many people around him, including her. For example, when she eventually left MOCA, “my way of doing the next chapter of my life was very bounced back by Noah Davis,” she explained. “I think if Noah could build an underground museum, I could do something outside of these institutions.”

“Noah Davis” was launched by Das Minsk of Barbican, London and Potsdam and was exhibited there from 7 September 2024 to 5 January 2025. The exhibition will be released in Barbican from February 6, 2025 to May 11, 2025, and will travel from May 11, 2025 to June 8, 2025 to June 8, 2025 to June 8, 2025 to June 8, 2025 to August 8, 2025.