On a recent summer day in Aspen, Colorado resort, artist Solange Pessoa is indoors, surrounded by bones in the basement of the Aspen Art Museum. She works purposefully, be careful not to disturb the layers of dirt that have been scattered on the floor, spreading coffee beans between burlap sacks, seeds are of great significance to the indigenous communities in Brazil and brightly colored powders. Elsewhere on the basement floor, Rose Three Towers consist of similar sacks. Regularly climb a ladder to reach the highest level of each tower.

The bags that make up the tower are stuffed with paper printed with photos Spiral dock and Brazilian musicians such as Milton Nascimento. However, Pessoa plans to fill these sacks with more materials in some way.

“70% of their texts are missing,” she said in Portuguese. “Generally, they overflow from the bag.” The texts will arrive in the coming days, before the opening of her exhibition.

Pessoa created the work in 1994 and exhibited it, although it was in a more modest form at Belo Horizonte, the city where she had lived for a long time. Over the past three decades, the artist has demonstrated a new iteration of the installation in Marfa, Texas to Bregenz, Austria. The latest iteration, Bags – Aspen version (1994–2025) is the star of her current performance at the Aspen Museum of Art, one of several solo museum exhibitions she has held outside of Brazil. She describes Bag As “the broader anthropology of America, through the traditions of the earth.”

Bag It is a symbol of Pessoa’s practice. It is vast and solemn and tries to tie humanity into the natural world. “I don’t like the separation of culture and nature,” she said. “My imagination of comprehensive philosophy, a philosophy of nature, brings culture into a part of nature.”

Solange Pessoa, Bags – Aspen version1994–2025.

Photo by Paul Salveson

Her practice has no disagreement between humans and ecology. Her sculptures are often recruited to bodily fluids, with abstract forms tending to recall animals that have deteriorated. Hair also appears in her works – especially Preface (Cathedral, 1990-2015), this is a huge installation wrapped in leather and fabric with tangled fabric. (This work is owned by the Rubell Museum in Miami, where it is its own ventilation reservoir.) These materials often appear along with feathers, fruits, dirt, and more.

“She is sensitive to anything in life,” said Thomas D. Trumer, director of Kunsthaus Bregenz. Bag. “That could be a plant, it could be a seed, it could be an animal, it could be an individual.” For Pessoa, “everything is relevant,” Trummer said.

In 2020, art historian Cecilia Fajardo-Hill wrote that Pessoa’s work “has only been recognized as it should in recent years and mostly beyond Brazil’s scope” – ascribed to Pessoa’s decisions about his own decisions, rather than art centers like rio de janeiro, such as rio de janeiro or s, rather than slim mi or sãopaulo noute soutate noute noute spotite spot of the Minas gera is gera is of sate of sgeara gera gera. Then there was a painful reaction that caused some fragments in her homeland: In 1995, Pessoa made a device called Jadem (Garden) Featured with leather, hair, blood and bull eyes, the public response was a situation where a Brazilian newspaper called on her to explain its meaning. “These are powerful works, but they didn’t make them scandalous,” she said at the time. She still never appeared in the Bienal de Sao Paulo version of Brazil’s top biennale.

Solange Pessoa, Sonhiferas i2020, at the 2022 Venice Biennale.

Photos Vincenzo Pinto/AFP via Getty Images

It is difficult to understand such a reception now, and Pessoa is beginning to gain international reputation. She appeared at the 2022 Venice Biennale and gained representation with Mendes Wood DM, one of Brazil’s most prestigious galleries. (Blum is another blue chip gallery that also represented her before announcing the end of its business earlier this month.) Her Aspen Art Museum exhibition matches another institutional solo exhibition at Tramway in Glasgow. “Time helped me grow,” Pessoa said.

It also helped her develop her own art, which is approaching a huge proportion. Deliria Deveras (2021 – 24) is one of the installations in her Aspen Museum of Art performance, occupying the entire gallery, containing many crystals made of silver blocks. These crystals weigh 20 tons.

Solange Pessoa, Deliria Deveras2021-24.

Photo by Paul Salveson

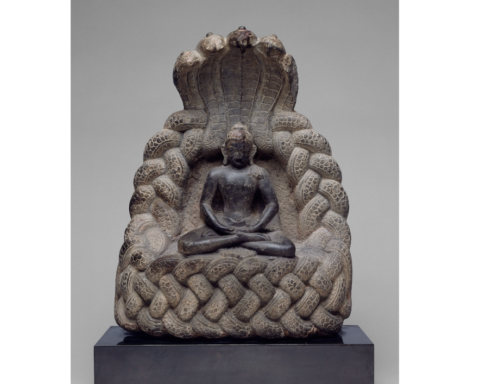

Deliria Deveras Recalling a famous Robert Smithson installation consisting of fragments of glass, Pessoa actually quotes Smithson and many Americans and Europeans who worked with him – Land artists, minimalists, Arte Povera sculptors – for her influence. Like those artists from the post-war era, Pessoa was fascinated by the idea that nature could lure into clinical gallery spaces. But her work has a clear spiritual dimension, which is lacking in her Western influence practice. “Absolutely modest, I feel like I’m working on the psychology of the relationship between human beings and the earthly gods,” she said.

Crystal entry Deliria Deveras Mining in the Brazilian city of Ferros, Pessoa was born in 1961. The mining industry is all around her – Minas Gerais has a long history of mineral extraction – so it naturally traps it in her art. “There is a psychological aspect to mining,” she said, calling herself Mineroopen Portuguese for “miners” and people from Minas Gerais.

Pessoa Preface yes). Although Pessoa herself does not consider herself a Catholic, she points to herself with “spiritual intuition” and says she draws inspiration from the rich tradition of Baroque art in the Brazilian church. Along with land artists and minimalists, she also appointed 18th-century sculptor Aleijadinho, whose works can be found in the church of Minas Gerais, one of her main inspirations. Pointing to all sacks Bagshe said: “Of course, these are all baroque – folding, verticality, excessive, emotional intensity.”

She attended art school in the 1980s, and in the 1990s she began making sculptures that had no major trend in Brazil: circles of bones, clusters of vegetable fibers hanging from walls and extending to the floor, like giants from the afters of the hay.

“She is the true outlier of her generation,” said Pessoa’s dealer Matthew Wood. “It’s not something people are doing, and certainly not what people value.”

Solange Pessoa, Bags – Aspen version1994–2025.

Photo by Paul Salveson

Some artists are starting to pay attention. Pessoa became friendly with Tunga, whose sculptures gave her the courage to use her hair in her art. She even became a member of the Galpão Berma collective with him. Through Galpão Bra, she also presented her work with artists such as Ione de Freitas and Nuno Ramos.

Even after being ridiculed in the media Jademthe 1995 installation featured a bull eye, and she didn’t want to conform to the trend. She works outdoors, and far from museums and galleries, she continues to make sculptures that may disturb the audience. Lesmalongas – Desterros (1998–2002), divided into five “cases” (four of which were performed on her family’s farm), including sculptures made of plastic, with combinations of lard and dirt. Some are dressed by screaming and crying performers as if Pessoa’s works are hurting them or forcing them to become like animals. Pessoa admits that her work does provide “sensory perturbation” and says, “I like when the work takes me out of my comfort zone.”

But for Pessoa, like Lesmalongas It’s not just about shocking the audience, they build a new relationship between people and their surroundings. “Vague [boundary] Between humans and non-humans, it is very important to her.

Pessoa has continued to take on this theme over the past few decades, although her work no longer seems to be designed to upset the way it once did. A few years ago, she began making paintings similar to animals that actually didn’t exist (“insects emerge from her mind, insinologically incorrect,” art historian Cecilia Fajardo-Hill once wrote); she recently began to showcase them frequently at the Venice Biennale 2022. She has started working in bronze medals, which lasts more than many of the organic matter she used in the 90s.

Solange Pessoa, Nihil Novi sole (fragment)2019–21.

Photo by Paul Salveson

She also invited soapstone, a material that once used to commemorate statues and fountains, for sculptures Nihil Novi soles (2019-21), appeared outside Aspen during the 2022 Biennale and is now on display on the roof of the Aspen Gallery. Pessoa enters the soft stone, carved in the form of leaves, collecting rainwater. In turn, the rain further changed the surface of her sculptures, which had been mottled from being exposed to elements.

Pessoa is keenly aware that her sculptures may not last forever and she even accepts her artistic qualities. “I feel the necessity of transientity, but on the other hand, I feel the necessity of eternity,” she said. “These contradictory philosophies are inseparable.”

Follow Me