The Louvre, France’s most famous museum, which welcomes some nine million visitors a year, is on the verge of an immense renovation. After director Laurence des Cars mentioned the institution’s deteriorating condition in a memo, French president Emmanuel Macron announced that the revamp will see Leonardo Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, one of the world’s most iconic artworks, move to a new exhibition space.

This transformation is simply one step in the museum’s history, last marked by an expansion in the 1980s featuring I.M. Pei’s startling and controversial entrance pyramid. Originally constructed in 1190 as a fortress, the Louvre became the main residence of French kings in 1546, and so it remained until Louis XIV moved to the Palace of Versailles in 1682. Almost every monarch contributed to its enlargement over the centuries, including Louis XIII and Louis XIV, both avid art collectors who made major additions. In 1793 the National Assembly decided to convert the entire building into a museum to hold and display France’s masterpieces.

The Louvre, which retains elements from the 12th century, the Renaissance, and French classical style, is said to have inspired the architecture of the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C., and the Metropolitan Museum in New York. It is home to half a million works of art, some 38,000 of which are on view. This impressive collection is divided into eight curatorial departments: Egyptian Antiquities; Near Eastern Antiquities; Greek, Etruscan, and Roman Antiquities; Islamic Art; Sculpture; Decorative Arts; Paintings; and Prints and Drawings. If you plan to visit but have no idea where to start, see our list of 30 must-see artworks below.

Note: The location of each artwork is listed below its description. You can refer to the Louvre’s interactive map to navigate.

-

The Code of Hammurabi

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Mbzt. The department of Near Eastern Antiquities holds the Code of Hammurabi, said to have been composed around 1755–1750 BCE by the sixth sovereign of the First Dynasty of Babylon. It is the longest, best-organized, and best-preserved legal text from the ancient Near East, engraved on a 7.4-foot basalt stele, or pillar, discovered in 1901 at the site of Susa in present-day Iran.

The top of the stele features an image of King Hammurabi himself with Shamash, the Babylonian sun god and god of justice. Below this figurative relief are about 4,130 lines of cuneiform text, most of it setting forth a wide range of criminal, family, property, and commercial laws, including the famous lex talionis: the eye-for-an-eye principle.

There are replicas of the stele in numerous institutions, including the headquarters of the United Nations in New York City and the Pergamon Museum in Berlin.

Near Eastern Antiquities, Room 227, Richelieu Wing, Level 0

-

Winged Bulls of Khorsabad

Image Credit: Copyright ©Musée du Louvre, RMN/Thierry Ollivier. King Sargon II reigned over the Assyrian Empire in the 8th century BCE. In about 713 BCE, he founded Dûr-Sharrukin (the “fortress of Sargon”) in the north of present-day Iraq, a new capital meant to become the largest city in the ancient world. His palace, intended as a symbol of omnipotence, was decorated with benevolent genii called aladlammû (“protective spirit”) or lamassu (“bull-man”). These 28-ton creatures, depicted from the front or the side, were each carved from a single alabaster block. They have the body and ears of a bull, the wings of an eagle, and a human face.

Their protective role was questioned when King Sargon II died in battle in 705 BCE. His body was never found, which led some to believe he was cursed; this is why his son and successor, King Sennacherib, decided to move the capital to Nineveh. The unfinished city of Khorsabad was rediscovered in 1843 by Paul-Émile Botta, the French vice-consul in Mosul. The excavation conducted under his aegis led to the rediscovery of a lost civilization, known only from the Bible and other ancient texts. Some of Botta’s finds, including this pair of bulls, made their way to the Louvre, where the world’s first Assyrian museum was inaugurated on May 1, 1847.

Near Eastern Antiquities, Room 229, Richelieu Wing, Level 0

-

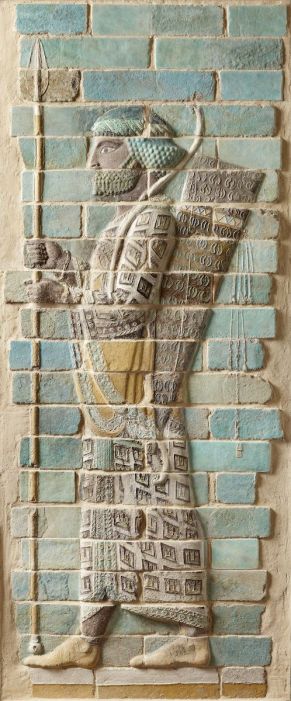

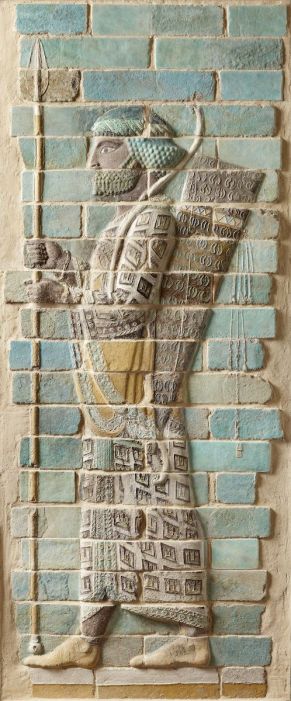

Frieze of Archers

Image Credit: Copyright ©2015 Musée du Louvre/Thierry Ollivier. Welcome to Susa, one of the oldest cities in the world. The capital of Elam, an ancient civilization centered in the far west and southwest of modern-day Iran, it was annexed in the 6th century BCE by the Achaemenid Persian empire. This is where Darius I (ca. 550–486 BCE) built a palace, the walls of which featured a polychrome brick frieze of bearded archers marching in profile holding spears with both hands and bows on their back.

Many believe them to be part of the elite infantry of 10,000 soldiers whom Herodotus named the Immortals. The frieze is made of siliceous brick with glazes of brown, white, and yellow, separated by thin cloisons (wires) to keep the colors from mixing. It was discovered in 1884 by French archaeologists Jane and Marcel Dieulafoy. Another 20 soldiers, found by Roland de Mecquenem toward the end of the excavation campaign, are also showcased in this wing of the Louvre.

Near Eastern Antiquities, Room 307, Sully Wing, Level 0

-

Statue of Ebih-II

Image Credit: Copyright ©2011 Musée du Louvre/Raphael Chipault. This 25th-century-BCE statue portrays a masculine blue-eyed figure sitting in a prayer position. According to a proto-cuneiform inscription on the back of the piece, it depicts Ebih-Il, superintendent of the ancient city-state of Mari in modern-day eastern Syria.

The 20.7-inch figurine is made of gypsum with inlays of schist, shells, and lapis lazuli. It was discovered in two pieces during excavations conducted in 1933 by French archaeologist André Parrot, the head on the pavement of the outer court at the Temple of Ishtar, and the body a few meters away..

Near Eastern Antiquities, Room 234, Richelieu Wing, Level 0

-

Statue of Karomama, Divine Adoratrice of Amon

Image Credit: Copyright ©Musée du Louvre/Christian Décamps. “I bring to the Louvre the most beautiful bronze ever discovered in Egypt,” wrote French philologist and orientalist Jean-François Champollion (1790–1832) soon after discovering this 1.9-foot masterpiece in 1829 at the Karnak Temple Complex near Luxor. Champollion thought the gracious effigy, adorned in gold, silver, and electrum, and dating back to 870 BCE, depicted Queen Karomama II, wife of pharaoh Takelot II of the 23rd Dynasty, when she in fact embodies Karomama I, daughter of the pharaoh Takelot I and wife of Osorkon II of the 22nd Dynasty.

Egyptian Antiquities, Room 337, Sully Wing, Level 0

-

The Great Sphinx of Tanis

Image Credit: Copyright ©Musée du Louvre, RMN/Christian Décamps. Towering more than 15 feet, the Great Sphinx of Tanis—a granite sculpture that may date back to the 26th century BCE—is the biggest sphinx preserved outside Egypt. Discovered in the ruins of the Temple of Amun-Ra in Tanis, the country’s capital under Dynasties 21 and 23, it was created much earlier, perhaps as early as the 4th Dynasty (ca. 2620–2500 BCE).

All that is left of its original inscription are mentions of pharaohs Amenemhat II (Dynasty 12), Merneptah (Dynasty 19) and Shoshenq I (Dynasty 22). The Louvre acquired this mythical creature with a human face, a lion’s body, and the wings of a falcon in 1826 from the collection of treasures amassed by Henry Salt, a British Egyptologist.

The sphinx was exhibited in the museum’s courtyard (today known as the Cour du Sphinx) between 1828 and 1848. In the mid-1930s it was transferred into the crypt designed by architect Albert Ferran to connect the two sections of the southern side of the Louvre’s Cour Carrée.

Egyptian Antiquities, Room 338, Sully Wing, Level 0

-

Seated Scribe

Image Credit: Copyright ©2015 Musée du Louvre/Christian Décamps. This sitting man—clad in a white skirt, with a half-rolled papyrus on his lap and a penetrating look on his face—is one of the Louvre’s icons. In ancient Egypt many pharaohs would have their servants immortalized as works of art so they could continue to benefit from their knowledge and services in the afterlife.

This male figure was sculpted in limestone probably around the period of the Old Kingdom, either under Dynasty 5 (ca. 2450–2325 BCE) or under Dynasty 4 (2620–2500 BCE). It was discovered in 1860 near a tomb at Saqqâra by French archaeologist Auguste Mariette.

The rock crystal, magnesite, and copper-arsenic inlays are what makes the scribe’s gaze so intense. Following its recent return from the Louvre-Lens, the Louvre’s sister museum in the north of France, you can lock eyes with the statue in Paris.

Egyptian Antiquities, Room 635, Sully Wing, Level 1

-

The Winged Victory of Samothrace

Image Credit: Copyright ©2014 Musée du Louvre/Philippe Fuzeau. Look how graceful she is, standing aloft a pedestal in the middle of the Daru staircase. The Winged Victory of Samothrace was named after the Greek island on which it was discovered in 1863 by French diplomat and archaeologist Charles Champoiseau.

A marble representation of Nike, the Greek goddess of victory, the sculpture was probably commissioned to thank the gods for a naval victory, and may date back to 190 BCE. It was found broken into 110 fragments—minus head and hands—and subsequently reassembled.

Champoiseau returned to Greece in 1879 to look for the missing parts, but in vain. Much of the right hand was eventually recovered, however: one half of the ring finger in 1875, the other half, along with the palm, in 1950. Victory!

Greek, Etruscan, and Roman Antiquities, Room 703 (Daru Staircase), Denon Wing, Level 1

-

The Venus de Milo

Image Credit: Copyright ©Musée du Louvre, RMN/Anne Chauvet. Like the Winged Victory, this armless marble statue was named after the Aegean island where it was found, Melos, in 1820. Also like the Winged Victory, the Venus de Milo is one of the Louvre’s “three great ladies,” as the museum terms them: The third is the Mona Lisa. No sooner was the statue discovered than it was purchased by the Marquis de Rivière, the French ambassador to Greece at the time, who donated it to the museum in 1821. The statue’s missing arms made her identification difficult, since Greek gods are usually recognizable by the objects in their hands. She was at first thought to be Amphitrite, the queen of the sea, but is believed to have held an apple, one of the attributes of Aphrodite, the goddess of beauty. Who is she really? No one knows for sure.

Greek, Etruscan, and Roman Antiquities, Room 345, Sully Wing, Level 0

-

Sarcophagus of the Spouses

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Jérémy-Günther-Heinz Jähnick. A woman and her husband rest on their elbows, their legs extended along a sort of dining couch called a triclinium. His arm lies across her shoulders, as she appears to be pouring perfume into his palm with one hand and holding a piece of fruit in the other (perhaps a pomegranate, symbol of eternity).

This 6th-century-BCE sculpture is a monumental cinerarium, a receptacle for the ashes of the dead. A masterpiece of Etruscan art famous for its creative use of terra-cotta, it was found in 1845 during excavations conducted by Marquis Campana in the ancient city of Cerveteri, and acquired in 1861 by Napoleon III specifically for the Louvre.

Etruscan Antiquities Galleries, Rooms 660, 662, 663, Denon Wing, Level 0

-

The Diana of Gabii

Image Credit: Wikipedia Commons/Marie-Lan Nguyen. This marble statue captures the simple gesture of a woman pinning her cloak. It was unearthed in 1792 by Gavin Hamilton at Gabii, not far from Rome, on the property of Prince Borghese. It has been on display at the Louvre since 1820.

The subject’s attire reveals her divinity: A short tunic with large sleeves, it is typical of depictions of the Greek deity Artemis (the Roman Diana), virgin goddess of hunting. The statue is attributed to Praxiteles, the most renowned 4th-century sculptor on the Attic Peninsula; her features are similar to those of other sculptures by Praxiteles, the Aphrodite of Cnidus and the Apollo Sauroktonos. Though the identification has been questioned on several grounds, there is no question that the Diana of Gabii is a strikingly high-quality example of the Praxitelian style, executed by the artist himself or perhaps one of his sons.

Greek, Etruscan, and Roman Antiquities, Room 529, Sully Wing, Level 0

-

The Pyxis of al-Mughira

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Marie-Lan Nguyen. “Blessing from God, goodwill, happiness and prosperity to al-Mughīra, son of the Commander of the Faithful, may God’s mercy [be upon him], made in the year 357.”

This inscription indicates the date and the recipient of this ivory vessel called a pyxis. It is believed to have been carved in one of the Madinat al-Zahra workshops, near modern-day Cordoba, Spain, but the identity of the giver remains unknown. Some think it was a coming-of-age present from a father to his son; others, a way to mock a prince who would never be next in line to rule. One thing is certain: The workmanship on this piece and particularly on its medallions—featuring two men picking up eggs from a falcon’s nest, two riders picking clusters of dates from a tree, two seated figures flanking a presumed servant, and a bull fighting a lion—is so refined that whoever commissioned it could only have been a wealthy man in a position of power.

Islamic Art, Room 185, Denon Wing, Level 1

-

The Monzon Lion

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons/G. Garitan. Is it purely decorative, or did it serve as a waterspout in a country—Islamic Spain—where fountains were of particular aesthetic importance? We cannot say. This bronze lion dating back to the 10th or 11th century CE was found in the 19th century by Spanish painter and fashion designer Mariano Fortuny in Monzón de Campos in northern Spain. On the animal’s back is a Kufic inscription, written in an alphabet often used to transcribe the Quran or wishes of good fortune. Baraka kamila/Ni’ma shamila means “Perfect blessing/Total happiness.” What more could anyone want?

Islamic Art, Room 185, Denon Wing, Level 1

-

Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons/C2RMF. Does she really need an introduction? Her enigmatic smile may be the most photographed in the world. Millions of visitors flock to the Louvre each year only to see her. Leonardo da Vinci’s masterpiece is thought to be the portrait of Italian noblewoman Lisa Gherardini, the wife of Francesco del Giocondo; hence her French name “La Joconde.”

Da Vinci (1452–1519) started the painting in 1503 or 1506 and finished it two years before his death. Acquired by King Francis I of France in 1518, this work is the only one to undergo a complete check-up every year at the C2RMF, the restoration and research center located beneath the Louvre, which speaks to how precious it is.

Paintings, Room 711, Denon Wing, Level 1

-

The Lacemaker by Johannes Vermeer

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons. Clad in a yellow bodice and holding a pair of bobbins in one hand and a pin in the other, this young woman seems engrossed in her work. Is she a noblewoman or a professional lacemaker? Nothing in the composition really gives it away. The book next to her could be the Bible, but the background is a blank wall.

This portrait was completed around 1669 by Dutch Master Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675). It is often compared to a painting with the same title by Caspar Netscher, another Dutch artist. Vermeer’s canvas first came to light at an Amsterdam auction in 1696. It was acquired by the Louvre in 1870.

Paintings, Room 837, Richelieu Wing, Level 2

-

The Coronation of Napoleon by Jacques-Louis David

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons. This is how it looked when Napoleon became emperor—or so you would be led to think. He commissioned this massive composition (33 by 20 feet) in 1804, and oversaw its execution closely. Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825), freshly appointed first painter of the court, took two years to complete it, and some changes were made along the way.

David had originally represented Napoleon with his hands down, but in the finished work he holds high the crown that he is about to put on Josephine’s head. Though his mother could not attend the ceremony, there she is, standing right in the center. This work of propaganda entered the royal collections in 1819. When it was transferred to the Louvre in 1889, a copy by the neoclassical master himself replaced it at Versailles.

Paintings, Room 702, Denon Wing, Level 1

-

Liberty Leading the People by Eugène Delacroix

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons. This iconic oil by Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) is often wrongly thought to depict a scene from the 1789 French Revolution. It actually commemorates the 1830 revolution that toppled King Charles X.

A woman clad in a loose yellow gown leads a group of people over a pile of corpses, holding a bayonetted musket that conveys her passion and determination. The tricolor flag in her other hand and the Phrygian cap on her head make her the personification of France, also known as Marianne.

Paintings, Room 700, Denon Wing, Level 1

-

The Slaves by Michelangelo

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Shonagon. Commissioned in 1505 by Pope Jules II for his tomb in Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome, Dying Slave and Rebellious Slave are the work of Michelangelo (1475–1564), sculpted between 1513 and 1515. The pope died before the pieces were finished, and the artist offered them in 1546 to his friend Roberto Strozzi, who in turn gave them to King Francis I.

After moving around for two centuries from the castles of Écouen and Richelieu to the Hôtel d’Antin, both works entered the Louvre in 1794; they recently underwent a thorough restoration. Now the pair is back for everyone to admire in the Michelangelo Gallery.

Sculptures, Room 403, Denon Wing, Level 0

-

Mary Magdalene by Gregor Erhart

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Leyo. This woman standing in contrapposto is Mary Magdalene, a sinner who repented and joined Jesus’s disciples. Legend has it she spent the rest of her life wrapped, not to say dressed, in her own hair. The limewood sculpture by Gregor Erhart (1470–1540) was probably intended for a church dedicated to the saint in the Dominican monastery in Augsburg, Germany. It later became part of German dealer Siegfried Lämmle’s collection, and the Louvre acquired it in 1902. It was taken to Germany during the Nazi occupation and returned to the Louvre after World War II. The base and front of the feet were restored in the 19th century.

Sculptures, Room 169, Denon Wing, Level 1

-

The Marly Horses by Guillaume Coustou

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Jastrow. In 1739 Guillaume Coustou (1677–1746) began turning blocks of Carrara marble into two life-size rearing horses, each managed by a vigorous groom. Louis XV commissioned the sculptures for the trough at the entrance of the Château de Marly, which Impressionist Alfred Sisley (1839–1899) later painted.

In 1794 the pieces were moved to the Place de la Concorde in Paris. In danger of damage from annual July 14 military parades, they were taken from there and installed in the Louvre in 1984, in a dedicated space named Marly Court, and replaced with copies by Michel Bourbon. The Marly Horses were an inspiration to the Romantics, especially to Théodore Géricault, known for his numerous depictions of horses.

Sculptures, Room 102, Richelieu Wing, Level 1

-

Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss by Antonio Canova

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Jean-Pol Grandemont. The myth of Cupid and Psyche is a classic story of lovers separated, sorely tested, and finally reunited. In the climax, Cupid’s kiss awakens Psyche. Colonel John Campbell, a Welsh politician and art collector, commissioned Italian master sculptor Antonio Canova (1757–1822) to capture this moment of rapture in 1787. It was later acquired by a French military commander, Joachim Murat, Napoleon’s brother-in-law, and eventually found its way to the Louvre. A second version made for Prince Nikolai Yusupov in 1796 is now in the Hermitage, in Saint Petersburg, and the plaster model is in the Metropolitan Museum’s collection. This sculpture is deemed a masterpiece of Neoclassical art, but the emotion conveyed by the lovers’ reunion foreshadows the emergence of Romanticism.

Sculptures, Room 403, Denon Wing, Level 0

-

The French Crown Jewels

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Cristian Bortes. Art within art: The room holding the Crown Jewels is just as extraordinary as the jewelry itself. These treasures were part of the 800-piece collection of King Louis XIV, who had the greatest painters, gilders, and sculptors of his time design a chamber in the Louvre to display them. The Galerie d’Apollon (named for the sun god, Apollo, with whom the king identified) was completed in 1850 under the aegis of architect Félix Duban. For the ceiling, Eugène Delacroix created a 128-foot-wide painting, Apollo Slaying the Serpent Python.

The oldest gem here may be the “Côte de Bretagne” spinel; it belonged to Anne de Bretagne, who became the Duchess of Brittany in 1488. The display also includes the Regent, the Sancy, and the Hortensia diamonds, which used to adorn royal garments, as well as emerald pieces that once belonged to Empress Marie Louise, second wife of Napoleon, and elements carved from agate, amethyst, lapis lazuli, and jade.

Decorative Arts, Room 705, Denon Wing, Level 1

-

Marie Antoinette’s Cylinder Desk

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Tangopaso. The secretary or cylinder desk was invented around 1760 by Jean-François Oeben (1721–1763), cabinetmaker to Louis XV. This innovative writing desk was closed by a quarter-cylinder-shaped cover with flexible slats to hide the compartments and drawers inside.

In 1784 Marie Antoinette, wife of King Louis XVI, commissioned Jean-Henri Riesener (1734–1806) to design a secretary for her new apartment in the Tuileries palace. With a wide range of motifs (floral garlands; laurel branches; ribbons in bronze frames; and allegories of Music, Painting, and Sculpture), this sophisticated piece of cabinetry made of amaranth, sycamore, and rosewood reflects the ill-fated queen’s sophisticated taste. The Louvre acquired the desk in 1901.

Decorative Arts, Room 632, Sully Wing, Level 1

-

The Napoleon III Apartments

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Daniel Perez Sutil. A visit to the Napoleon III apartments at the Louvre is a journey back in time. These sumptuous rooms, decorated in gold and velvet, and filled with refined paintings, were created in 1861 for Achille Fould, the minister of finance, as a residence in the brand-new Richelieu wing. A masked ball was thrown to inaugurate the apartments, and many festivities followed, often attended by the imperial couple themselves. The large drawing room could be transformed into a theater with a 250-guest capacity.

After an 1871 fire during the Paris Commune, the Ministry of Finance was forced to move into Fould’s apartments, and stayed there until 1989. The apartments, long closed to the public, opened again to visitors in 1993.

Decorative Arts, Room 545, Richelieu Wing, Level 1

-

The Tomb of Akhethetep

Image Credit: Copyright © 2003 Musée du Louvre, Dist. GrandPalaisRmn/Christian Décamps.

In 1903 the remains of a 4,000-year-old mastaba, a flat-roof tomb for a royal official, were found in Saqqâra, Egypt. It was identified as that of Akhethetep, who was simultaneously priest of Heka, priest of Khnum, and priest of Horus.

The decorated chapel of this antique complex was relocated the same year to the Louvre’s Denon (South) Wing, and moved to the Sully (East) Wing, its current location, in 1934–35. In 2017 it was decided to dismantle it once more, and to scan it and restore it to its original dimensions. The ambitious project, sponsored through a crowdfunding campaign, took two years, starting with its disassembly in 2019.

Egyptian Antiquities, Room 333, Sully Wing, Level 0

-

Egyptian Mummy

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Shonagon. This anonymous man, found resting in his coffin and sarcophagus, was mummified so that his soul might lead a pleasant afterlife. Accordingly, his body had to be emptied of viscera, and filled with rock salt, coated with ointments, resins, and oils, then wrapped in up to 35 layers of thin strips of linen cloth.

Little is known about this specific mummy, acquired in 1826 as part of English diplomat Henry Salt’s collection. The deceased was 65.3 inches tall and probably lived during the Ptolemaic period, the last and longest of ancient Egypt’s dynasties, from 305 BCE until its incorporation into the Roman Republic in 30 BCE.

Egyptian Antiquities, Room 322, Sully Wing, Level 0

-

Baptistère de Saint Louis

Image Credit: Copyright © 2009 Musée du Louvre, Dist. GrandPalaisRmn/Hughes Dubois. This object was made from a single sheet of hammered brass, inlaid with silver and gold. It depicts a procession of princes on horseback, courtiers and hunters, and species of animals from dogs to falcons to cheetahs. It was called Baptistère de Saint Louis, though it has nothing to do with King of France Louis IX, also known as Saint Louis (1214–1270), since it was produced almost a century after his reign, under the Mamluk dynasty that ruled Egypt and Syria from 1250 to 1517.

In 1606 the basin was used as a baptismal font for the young Louis XIII, and far later, for Napoleon III’s son. Its origins, however, remain uncertain. Did the item first serve as a ritual washing bowl at the Mamluk court, or was it commissioned by a Christian patron, instantly joining the French royal collections?

Islamic Art, Room 186, Denon Wing, Level 2

-

Poetic joust panel

Image Credit: Copyright © 2012 Musée du Louvre, Dist. GrandPalaisRmn/Raphaël Chipault. This Iranian mosaic panel in shades of blue, green, and yellow shows four figures engaging in what seems to be a literary contest in a lush garden. In the center, two turbaned men kneel face to face. Each is holding a safina, an oblong poetry book. The one on the left appears to be declaiming verses; the one on the right to be writing a poem. The large ceramic tiles used for this composition were particularly popular in 17th-century Iran.

The origin of this work, purchased by the Musée du Louvre in 1893, is unknown. Comparison with similar panels in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Victoria & Albert Museum in London suggests that it came from Isfahan’s Chehel-Sotoun royal pavilion, where Shah Abbas II received dignitaries and ambassadors. All three might even belong to the same series.

Islamic Art, Room 186, Denon Wing, Level 2 (Currently not on view)

-

Pietà by Rosso Fiorentino

Image Credit: Copyright © 1998 GrandPalaisRmn (Musée du Louvre)/René-Gabriel Ojéda. Supported by St. John on the right and the Magdalene at his feet, Christ lies unclothed across the center of the painting, the Virgin Mary at left falling back in grief, her arms outstretched in a cross. A woman behind her prevents her from falling. Giovanni Battista di Jacopo, nicknamed Rosso Fiorentino (“the Florentine Redhead”), executed the piece between 1530 and 1540, at the request of Constable Anne de Montmorency, a favorite of King Francis I.

This masterpiece of Mannerism, transposed onto canvas in 1802, has undergone several restorations. That of 1992–97 led to a spectacular discovery: Rosso had painted a deposition scene before creating his Pietà. Between both compositions lies a layer of black paint that made it easier for the artist to start over. Fun fact: The painting as we know it today briefly appears in the video for the song “APESHIT” by the Carters (Beyoncé and Jay-Z).

Paintings, Room 712, Denon Wing, Level 1

-

The Virgin of Jeanne d’Évreux

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Shonagon. This 27-inch gilded silver statue incorporating stones and pearls depicts the Virgin Mary holding the Infant Jesus in her arms, as well as a fleur-de-lis of gold and crystal; it contained relics of her clothing, hair, and milk. This kind of reliquary derives from a Byzantine model known as the “Virgin of Tenderness.”

The base is supported by four lions and adorned with enamel plaques depicting episodes in Christ’s life on earth: Annunciation, Visitation, Nativity, Announcement to the Shepherds, Adoration of the Magi, Presentation in the Temple, Flight into Egypt, Massacre of the Innocents, Resurrection, Descent into Limbo.

This artwork belonged to Jeanne d’Évreux, Queen of France from 1324 to 1328, who donated it to the Abbey of Saint-Denis in 1339, as suggested by the engraving on the plinth.

Decorative Art, Room 503, Richelieu Wing, Level 1

Follow Me